William the Conqueror and the Harrying of the North 1069-70: Contexts and Perspectives

- Date

- 14 Nov 2017

- Start time

- 7:30 PM

- Venue

- Tempest Anderson Hall

- Speaker

- Professor David Bates, UEA

Professor David Bates, University of East Anglia

Author of “William the Conqueror” in the “English Monarchs Series” from Yale University Press

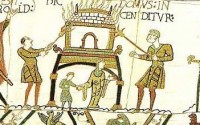

This lecture will reflect on the broader context of the infamous Harrying of the North including both the period prior to the Norman Conquest in 1066 and the place of violence against non-combatants in medieval Europe.

Joint lecture with the Centre for Medieval Studies, University of York.

Part of the “Normans in the North” programme

Members’ reports

Professor David Bates outlined, to a capacity audience, some of the issues he considered in writing his biography of William I. By the time William turned his attention to England, on the death of Edward the Confessor, in 1066 he had consolidated his hold over the Duchy of Normandy and the neighboring county of Maine. Although taking a large army across the sea was dangerous it was also a potential new source of reward for his nobles. After defeating Harold, William was crowned King of England by Archbishop Ealdred, in Westminster Abbey at Christmas 1066. Ealdred can be seen as either a peacemaker or an appeaser but his death in 1069 and the presence of the last Wessex claimant to the throne: Edgar Atheling encouraged Anglo-Danish rebellion in the North. In 1069 William also lost Maine in France and taking his army north to York to subdue the area can be seen as demonstrating the legitimate anger of a ruler against a rebellion.

Orderic Vitalis records the Harrying “destroying all crops, herds, chattels and food of every kind”. Research has shown that more than 100, 000 people died of starvation, just replacing the 80,000 slaughtered oxen would take many years, a minimum of five years to nurture and train one animal. Difficult not to condemn the loss of livelihoods but in the context of medieval kingship violence was seen as a legitimate course of action.

Catherine Brophy

A capacity audience was treated to the thoughts of an experienced historian revisiting evidence, for his biography of William I. His was a radical re-evaluation of the Conqueror, and of the difficult question of using legitimate violence against rebellious non-combatants. William was crowned King of England, in Westminster Abbey at Christmas 1066, by Archbishop Ealdred, an English prelate who provided a pacific link between the reigns of Edward, Harold and William. When he died in 1069, one of the restraints on William’s treatment of the English was removed. So, when the presence of the last Wessex claimant to the throne, Edgar Atheling, encouraged Anglo-Danish rebellion in the North, William reacted vengefully by taking his army north to York to subdue the area, and take what he saw as legitimate retribution.

The chronicler Orderic Vitalis recorded the destruction of “all crops, herds, chattels and food of every kind,” including 80,000 trained oxen, each of which would take a minimum of five years to replace. More than 100,000 people died of starvation. That the North recovered is largely due to the resilience of the people; but the loss of livelihoods in the context of a medieval king’s right to use violence against unarmed citizens, even when seen as a legitimate course of action, remains problematic.

Carole Smith