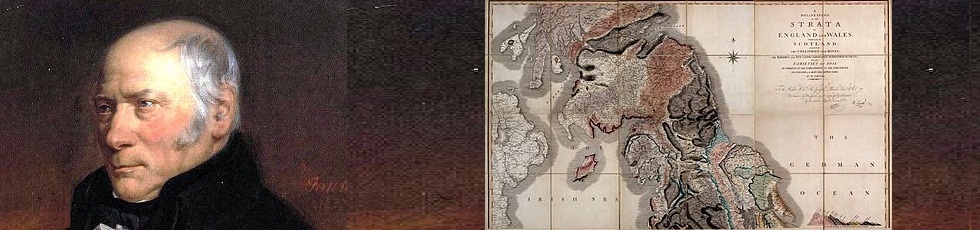

Smith and his 1815 map

The geological map project was inspired by the two hundredth anniversary of the publication of a famous map – described as ‘The map that changed the world’ by Simon Winchester, in his book of the same name.

Much has been written about the largely self-taught individual, who single-handedly surveyed the whole country and devised a map to represent the underlying structure. The following account is taken from a display mounted by the Yorkshire Museum, which celebrated the bicentennial by refurbishing its own original copy and mounting it in a new display cabinet. They have kindly agreed to make the accompanying text available for us to put on this website.

Further information on William Smith is available as part of our Yorkshire Scientists section. Click on William Smith biography

WILLIAM SMITHS GEOLOGICAL MAP AT THE YORKSHIRE MUSEUM

A delineation of the strata of England and Wales, with part of Scotland…

WHO WAS WILLIAM SMITH?

William Strata Smith (1769-1839) is often known as the Father

of English Geology. He is best known for his geological

map of England and Wales, which was first published

in 1815. He was an exceptional geologist, who,

despite his limited formal education,gained work

as a canal surveyor from the age of 18. He travelled

the country, digging into the ground to identify

where best to cut new canals. He soon noticed that

rock layers strata and fossils were found

in the same order, even when separated by great

distances. He realised that he could join this information

up to create the first ever geological map of a country,

and help all sorts of people, from farmers to civil engineers.

THE PIONEER MAP MAKER

For his 1815 map of England and Wales, Smith was ambitious.

He commissioned a huge new base map that allowed

more space for his geological information.

The geology on each map was hand-coloured in

Smiths unique style,and he inspected each one

himself. Despite the huge mount of work and

money that went into the map, only 400 copies

were ever produced. Smith couldnt

cover the costs of the project, and his work was

overshadowed by that of the new Geological Society

of London. He sold his fossils to the British Museum,

but this was not enough to escape spending ten weeks

in Londons Kings Bench Debtors Prison in1819.

He resumed his high quality geological work when he left

prison, but he was 62 before his scientific talent and contributions

were finally recognised by the Geological Society.

his personal loss was the public gain;

his individual strength

performed a national work

Phillips 1844, Memoirs of William Smith

WILLIAM SMITH IN YORKSHIRE

Smith, after being released from

debtors prison in 1819, travelled the

North of England with his nephew

and apprentice John Phillips. They

lectured together at Philosophical

Societies across Yorkshire, and Smith

was resident in the Scarborough area

for over a decade. He designed the

Rotunda Museum in 1829, and

supplied the building stone for it

and the Yorkshire Museum.

THE NEW YORKSHIRE MUSEUM

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society, founded

in 1822, opened the Yorkshire Museum in 1830

They took on John Phillips as their

first Keeper of Collections, from 1825-1840.

Phillips had become an accomplished

geologist after training with Smith.

He published the first geological timescale,

invented the term Mesozoic as a major

division of geological time, held academic

posts in London and Oxford, and

corresponded with Charles Darwin.

THE YORKSHIRE MUSEUMS MAP

The Yorkshire Philosophical Society, founders of the Yorkshire Museum,

purchased one of Smiths large maps in 1824, at the time that he and

Phillips gave a series of lectures for them. Each map was unique, not

only because of the hand colouring, but also because Smith continued

to update the information published on it. There are over 20 different

versions known to have been circulated as a result. However, they are

all painted onto the same base map, dated 1815, so it can be difficult

to tell them apart and to date each version. This map is a later edition,

published after 1819. It is the only one known to exist with geological

information entered for France. There are approximately 100 maps

remaining today, many of which are in private hands.