John Phillips

John Phillips FRS (1800-1874)

by Rod Leonard

Overview

John Phillips, the son of an excise officer, was orphaned at the age of seven but rose to become one of the most respected figures in British geology and the gentrified academic establishment. By introducing a statistical approach to palaeontology, he developed William Smiths ideas on using fossils to prove the correct stratigraphy of geological deposits. He thus identified and named the major geological eras Palaeozoic, Mesozoic, and Caenozoic, and demonstrated the mass extinctions between them. Phillips was a prolific academic and popular science author, and was also active in the fields of astronomy, electromagnetism, zoology, botany, meteorology, scientific instruments, museum design, and surveying.

John Phillips was born on Christmas Day, 1800 at Marden, Wiltshire. When both his parents died in 1808, he was supported by his remarkable uncle, William Smith. A largely self-taught surveyor, who spent his income on his passions of fossils and geology, Smith ultimately became known as the Father of English Geology. He did his best to provide his nephew with a good education under difficult circumstances.

In spite of being moved between four different schools, Phillips quickly became confident in Latin, French and mathematics, and learned enough Greek for him to build on in his later career. Smith’s financial problems forced Phillips to leave school when he was about fourteen, but he was then able to study for a year under his uncles friend the Rev Benjamin Richardson, who helped him to develop a deep love of natural history. Formal education stopped at the age of fifteen, when he began to work as his uncle’s assistant travelling the country with him on pioneering geological field trips. They were often in poverty – indeed Smith was imprisoned for debt in 1819. On his release, they travelled extensively in the north of England as itinerant surveyors, also using their travels to work on Smiths geological maps.

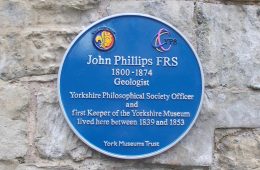

In 1824, Phillips began a long and mutually beneficial relationship with the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, described in more detail later. In February 1831, while serving the society as both Keeper and Secretary, he was asked by the Scottish Physicist David Brewster to facilitate hosting the inaugural meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. With help from the recently retired first President of the YPS, William Vernon Harcourt, Phillips ensured that the conference, which took place at the end of September, was a great success. He was appointed as first secretary of the newly formed association serving from 1832 to 1863, and as President in 1865.

1834 saw a breakthrough in his academic career, when he was appointed to the Chair of Geology at Kings College, London, published a Guide to Geology, and was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. His Report on the Geology of Cornwall, Devon, and West Somerset was published in 1839, followed by Figures and Descriptions of Palaeozoic Fossils of Cornwall, Devon, and West Somerset in 1841, in which year he joined the British Geological Survey.

In 1844, Phillips was appointed Professor of Geology at the University of Dublin, and was awarded the prestigious Wollaston Medal by the Geological Society of London. He also published Memoirs of William Smith LLD, Author of the Map of the Strata of England and Wales, by his Nephew and Pupil, John Phillips FRS, FGS, etc. In this, he objectively confirmed his uncles priority to many major contributions to geology.

Phillips published the Geological Survey of the Malvern Hills in 1849. Interestingly, his sister Anne made a significant contribution by refuting Murchisons accepted view of their formation. In this year too, he was appointed as a Commissioner to enquire into and report on ventilation in coal mines, which led to the introduction of colliery inspectors.

His long career at the University of Oxford started in 1853, when he was appointed Deputy Reader in Geology. He was elevated to Professor in 1856 and was also elected as President of the Geological Society of London. Between 1856 and 1865, he wrote a number of astronomical papers which he communicated to the Royal Society.

Although a devout Christian, Phillips engaged in a scientific debate with Charles Darwin on the age of the earth. In 1860 Phillips argued that geological evidence demonstrated this was much greater than 100 million years, compared with the religious teaching of about 6000 years. In the same year, he published his book Life on Earth: its Origin and Succession

Connections with York & Yorkshire

From about 1819, Phillips helped Smith with surveying commissions in Yorkshire; with the 1820 update of Smiths famous 1815 geological map; and with the County Map of Yorkshire published in 1821.

In 1824, he helped with Smiths series of lectures to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, and made an immediate impact. He was paid £20 to arrange the YPS fossil and geological collections, and was made an Honorary Member of what was then still an exclusive Society.

In 1825 he was appointed by the YPS as Keeper of its Museum and draughtsman to the Society, commencing 1 January 1826. His salary was £60 p.a. plus lecture fees for 3 days a week, from 10am to 4pm, for nine months each year. His career and social elevation were thus effectively launched by the Yorkshire Philosophical Society. Phillips proved to be an excellent lecturer. He toured extensively in the region, and characteristically donated half of his lecture fees for the purchase of display cabinets. He also made many donations of valuable specimens to the Society.

In a somewhat bizarre incident in 1831 he was famously chased around the YPS Gardens by a bear that had escaped from the YPS menagerie. The bear was prudently offered to the newly opened Royal Zoological Gardens in London. The zoo accepted the gift, and instructed that the bear be sent to them as an outside passenger on the stage coach!

Phillips made countless geological field trips throughout Yorkshire leading to major works specific to the county. These included Illustrations of the Geology of Yorkshire Part 1 (1829), which included a detailed geological map of eastern Yorkshire. Part 2, which covered the Mountain Limestone in the northwest of the county, followed in 1836. These remarkable volumes remained the main reference sources for Yorkshire geology until the mid 20th C. Also significant were The Rivers, Mountains, and Sea-Coast of Yorkshire (1853), and a Geological Map of Yorkshire (1855) which included three cross sections of the strata.

Phillips was a close friend of Thomas Cooke, the instrument and telescope maker. He bought Cooke’s first telescope (2.4’’) in about 1839. In about 1852, Phillips bought a 6.25’’telescope and a clock drive from Cooke, and in July 1853 took some of the first photographs of the moon from his garden in York.

As early as May 1851, Phillips, Cooke and William Gray repeated and confirmed Foucault’s famous pendulum experiment of February 1851, by building a pendulum in York Minster.

Pressure of work finally forced Phillips to resign as Keeper of the Yorkshire Museum in December 1840, but he viewed York as his primary home, at least until 1853 when he moved to Oxford. He buried his beloved sister Anne in York Cemetery in 1862, with the clear intention that this would eventually be his own resting-place. He continued his link with the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, and served the Society in various capacities including Secretary, Curator, Honorary Curator, and Vice President, which role he filled until his death.

Phillips died in Oxford after a fall. His body was accompanied to Oxford station by 150 mourners. After arrival at York, he lay in state overnight in the Yorkshire Museum. The next day, 30 April 1874, the Minster bells were tolled for 90 minutes before his funeral. He was buried in York Cemetery alongside his sister, under a modest gravestone.

Connections with St Marys Lodge (1838 to 1870)

St Marys Lodge has an interesting history. It was added to the 12th C gatehouse to St Marys Abbey during refurbishment in 1470. It survived the dissolution of the monasteries, and served a number of different uses, including as a prison until the early 1700s. In 1835, the parcel of land on which It stands was added to the grounds of the Yorkshire Museum. Known at that time as Gateway House, and being used as the Brown Cow public house, it was in poor repair. In 1838 Phillips, whose career was blossoming, offered to undertake major repairs and refurbishment at his own expense, in order to make a home for himself and his sister, provided a substantial garden was included in a 30 year lease at £15 pa. The YPS eventually agreed to a lifelong lease of the Gateway and the Garden, jointly with his sister Anne and starting in April 1839 when the existing tenant quit, for an even lower initial rent of £7 10s. The refurbishment was finished later in 1839 and Phillips renamed the building St Marys Lodge.

During the long period of the lease, although he visited regularly, Phillips was often based out of York. He therefore sub-leased the Lodge for significant periods, though records of this are incomplete. One tenant wrote to him in 1844 about the beauty of the garden he had taken over. Other tenants were in residence in 1854 and 1858. Phillips himself was almost certainly in residence 1839 1841 and 1849-1853, and possibly intermittently at other times. Interestingly, in 1850 Phillips returned home to find the Water Company had erected an engine chimney in view of his premises, to a much greater height than had been agreed. He wrote a strong letter of protest, which resulted in the chimney being shortened. The 1851 census for St Marys Lodge shows the residents to be John Phillips (aged 50, FRS and formerly Professor of Geology at Kings College London and at Trinity College, Dublin), Anne Phillips (his sister, aged 48, and described by Phillips as an Annuitant),and two servants (a Cook and a Housemaid). Phillips finally relinquished the lease in 1870 under favourable terms.

Bibliography

British Geological Survey website: www.bgs.ac.uk

Collinge, W.E. 1924. John Phillips. Yorkshire Philosophical Society Annual Report 1924.

Encyclopedia Britannica 9th Edition :http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/456569/John-Phillips

Geological Society website, https://www.geolsoc.org.uk/

Morrell, Jack. 1989. The legacy of William Smith: the case of John Phillips in the 1820s.

Archives of Natural History (1989) 16(3), 319-335

Morrell, J. 2005. John Phillips and the business of Victorian science. Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

Orange, A.D. 1971. John Phillips and the Yorkshire Philosophical Society.

Yorkshire Philosophical Society Annual Report 1971.

Orange, A.D. 1973. Philosophers and provincials the Yorkshire Philosophical Society from

1822 to 1844. Yorkshire Philosophical Society.

Oxford Dictionary of National Biography; John Phillips

Rubinstein, D. 2009. The nature of the world the Yorkshire Philosophical Society 1822-2000.

Quacks Books, York

Strange Science website: http://www.strangescience.net/phillips.htm

Yorkshire Philosophical Society, Council Minutes, (extracted by Dr P J Hogarth)

Yorkshire Philosophical Society, Annual Reports.

I

Image Credits: [1] Wiki Commons: Source: H.B. Woodward (1907). The history of the Geological Society of London.Banner photographs Rod Leonard. Map from Phillips Illustrations of the Geology of Yorkshire Private Collector Photographed Rod Leonard. Engraving N Whittock, property of YPS