Henry Clifton Sorby

Henry Clifton Sorby

by David Rowe

Henry Clifton Sorby was born in the Attercliffe district of Sheffield, the only child of an affluent partner in a family firm of edge-tool manufacturers who also had a coal mine on his estate. Sorby was educated at a private school in Harrogate and later at the Sheffield Collegiate School where a book that he won as a mathematics prize inspired him to study science.

He left school at 15 and since at that time university degrees in science were not available he studied instead at home for four years with a private tutor, the Rev. Walter Mitchell, who had a broad scientific background and an interest in crystallography. When Sorby was 21 his father died leaving him a substantial fortune and he moved (with his mother) to a house in Broomhill on a site now covered by part of the Royal Hallamshire Hospital. There he set up a well-equipped laboratory and workshop, his base for independent research for the rest of his life. His research was wide-ranging and he continually worked on a number of topics concurrently, predominantly but not exclusively geological. In total he published about 240 papers.

Early on Sorby took an interest in microscopy and, following in the footsteps of Sir David Brewster (1781-1868) and William Nicol (1770-1861) in Edinburgh, he learned to make transparent thin sections of opaque natural materials such as fossil wood, teeth and bones for examination, using a polarizing microscope. Sorby, however, also made thin sections of rocks and was the first to appreciate the value of microscopy in the investigation of mineral composition and rock structure. From 1849 he prepared many thin sections, over 1000 of which are now held by the University of Sheffield. His sections of non-calcareous rocks were ground to about a thousandth of an inch, close to the 0.03 mm now the standard thickness for petrological work. In 1851 Sorby read a paper to the Geological Society of London on The microscopical structure of the calcareous rocks of the Yorkshire coast and in 1856 published On the microscopic study of crystals indicating the origin of minerals and rocks in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society.

Photomicrograph of a volcanic lithic fragment (sand grain); upper picture is plane-polarized light, bottom picture is cross-polarized light, scale box at left-centre is 0.25 mm. (2)

This laid the foundations of microscopical petrology which became a cornerstone of geology, especially after the publication in 1866 of the very influential two-volume Lehrbuch der Petrographie by Ferdinand Zirkel (1838-1912); Sorby had introduced Zirkel to his methods on meeting him in Germany in 1861. Another innovation of Sorbys (publicized in 1877) was the use of a quartz wedge, an accessory now routinely used in the determination of the optical sign of birefringent minerals.

A byproduct of Sorbys microscopical work was the early study of liquid inclusions in quartz in granites from which he made deductions about the depth at which the granites had consolidated. Another of Sorbys early interests is illustrated by the talk he gave in June 1850 to the Yorkshire Philosophical Society On the drifting of the sandstone beds of the oolitic rocks of the Yorkshire coast. (I am indebted to Alan Cochrane for drawing my attention to a summary of this talk in the Proceedings of the Yorkshire Philosophical Society, Volume I, Part II, 111-113, 1855). Sorbys investigations in this area, which started in 1847 when he was only 21 and involved field observation, experimental work and microscopy, were pioneering work in sedimentology.

A visit to Wales in 1851 stimulated Sorbys interest in slaty cleavage, a controversial topic in the 1850s. As a result he came into conflict with eminent geologists of the day including Sir Henry de la Beche, the first Director of the Geological Survey; but from meticulous macroscopic and microscopic observation of detail he concluded that the cleavage was associated with reorientation of particles of mica under the influence of anisotropic pressure, and his view prevailed. His work extended over some years but an early paper, On the nature of slaty cleavage, appeared in the Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society in 1853. It was his work on slaty cleavage that established his reputation nationally and led to his election in 1857 to the Fellowship of the Royal Society.

Sorbys interest in petrology extended to meteorites, polished and etched surfaces of which he examined by reflected light microscopy. Later he used the same technique to study samples of iron and steel, thus pioneering microscopic metallography. As an offshoot of this work he developed a spectrum microscope, a combination of microscope and direct vision spectroscope. With this instrument he ventured into the field of spectroscopic examination of a wide range of natural pigments in biological materials. His microspectroscopic study of blood led to forensic applications.

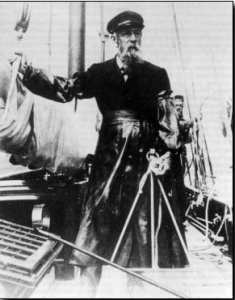

In 1878 Sorby bought Glimpse, a yawl or large yacht which he equipped as a floating laboratory. Employing a crew of five he spent most of the next 25 summers cruising, mainly off the east coast of Britain.

Work during this period included a study of silt and sewage movements in the Thames estuary for a Royal Commission but his interests were wide, with marine biology now dominant.

From 1902 Sorby was crippled and he spent the remaining years of his life working over the notes he had accumulated over the years. This resulted in his final, highly regarded, major paper On the application of quantitative methods to the structure and history of rocks read to the Geological Society shortly before his death and published posthumously in the Quarterly Journal. Sorby was the (first) President of the Royal Microscopical Society 1875-77, President of the Mineralogical Society 1876-79, and President of the Geological Society 1878-80. He also served on the Council of the Royal Society. From the age of 20 he was a lifelong member of the Sheffield Literary and Philosophical Society to which he often presented results of his researches before publication more widely; he was elected its President seven times and also became the first President of the Yorkshire Naturalists Union. From 1880 he worked with Mark Firth to promote higher education in Sheffield and, after Firths death in 1882, he served as President of Firth College until 1897 when it merged with the local technical and medical schools to become University College, of which he became Vice-President; in 1905 the college became the University of Sheffield on the Council of which he was a member for the rest of his life.

Sorby was honoured internationally and in Britain he was notably awarded the Wollaston Medal of the Geological Society in 1869 and the Royal Medal of the Royal Society in 1874. The University of Cambridge conferred upon him an Honorary LL.D. in 1879. In 1907 when he was virtually confined to his house he received an address to the father of microscopical petrology, signed by the worlds leading petrologists, from the Geological Society on the occasion of its centenary celebrations. Sorbys name is commemorated today in: the Sorby Chair in Earth Sciences at the University of Sheffield; the Sorby Research Fellowship of the Royal Society; the Sorby Medal, the premier award of the Yorkshire Geological Society, for distinguished geological work associated with Yorkshire; and also in the name of the Sorby Natural History Society (originally the Sorby Scientific Society) which was formed in 1918 from the Sheffield Naturalists Club, the Sheffield Microscopical Society, and the Junior Naturalists Club.

Sorby died in March 1908 and was buried in the churchyard of Eccleshall Parish Church, Sheffield. His grave lies near the West Door of the church and is composed of two Scottish granites, from Peterhead and Rubislaw (Aberdeen), mounted on a sandstone plinth.

To find out more:

Anon. Sorby, Henry Clifton 1826-1908 geologist. Navigational Aids for the History of Science and Technology. http://www.nahste.ac.uk/isaar/GB_0237_NAHSTE_P0261.html accessed August 2012.

Clinging, Valerie (undated). Henry Clifton Sorby: Sheffields Greatest Scientist. Sorby Natural History Society, Sheffield.

Humphries, D. W., 2004. Henry Clifton Sorby. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, 51, 646-648.

Judd, J.W., 1908. Obituary. Henry Clifton Sorby (1826-1908) (With a portrait, Plate VI). Mineralogical Magazine, 15 (69), 180-184.

Kendall, Percy F, 1908. In Memoriam: Henry Clifton Sorby. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 16, 247-250.

Robson, Douglas A., 1986. Pioneers of Geology. Special Publication of the Natural History Society of Northumbria, Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Smith, Cyril Stanley, 2008. Sorby, Henry Clifton, Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography. Encyclopedia.com accessed August 2012

Wilcockson, W. H., 1947. The geological work of Henry Clifton Sorby. Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society 27, 1-22.

Yorkshire Geological Society Circular No. 536. Development of Scientific Methods in Sheffield: Henry Clifton Sorby FRS (Celebrating a Great Victorian Scientist). Programme for a field meeting in Eccleshall Parish Churchyard and 3 lectures at Sheffield University, 17 February 2007.

Image credits: 1) Sheffield City Council, Libraries Archives and Information: Sheffield Local Studies Library Picture Sheffield s08173; 2) Wiki Creative Commons; 3) Sheffield City Council, Libraries Archives and Information: Sheffield Archives MD2078/20