Fred Hoyle

Sir Fred Hoyle (1915-2001)

by Patrick Mason

Fred Hoyle is one of the better known British figures in science of the 20th century. His many contributions to science would in themselves justify this but it was also his engagement with the general public through various media, and his controversial ideas and almost stereotypical Yorkshireman character which made him into a household name. However, perhaps his lasting legacy in popular science culture is that he first coined the phrase Big Bang.

His parents, Ben and Mabel, lived in Gilstead near Bingley in the West Riding. Ben worked in the Bradford woollen industry while Mabel, having studied at the Royal Academy of Music, provided piano accompaniment to silent films at the local cinema. Fred was born on 24 June 1915 at home in Gilstead while the First World War was on. During the war, his father remarkably managed to survive action in the midst of the Battle of the Somme. By the time of his fathers return home in 1919, Fred had already started to show a talent in numeracy. Unfortunately such precociousness was not compatible with his first two schools and his early years in education were mainly spent playing truant. He eventually settled at Eldwick school and then gained a scholarship to go to Bingley Grammar School. Enthused by reading Arthur Eddingtons Stars and Atoms and having received a telescope for Christmas when he was ten, Freds interest in astronomy germinated. This interest and his talent for mathematics was nurtured by his tutor, Alan Smailes who helped him get through college entrance exams and also win a scholarship from West Riding County Council. This enabled him to go to Emmanuel College, Cambridge to study mathematics. After graduating Hoyle went on to study as a research student, initially under the supervision of Rudolf Pierls. A paper on the beta decay in atomic nuclei was co-authored with Pierls and Hans Bethe. However, after a disagreement with Pierls, Maurice Pryce took over as his supervisor and then, after Pryce moved, Hoyle ended up with the famous and distinguished Paul A.M. Dirac as his supervisor. Despite Dirac being a supervisor who did not want a student supervising a student that did not want a supervisor, the coupling worked well. His later research in this period included observation of interstellar hydrogen and the development of a theory, along with Ray Lyttleton, on the formation of stars by accretion. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1940. In 1939 he met Barbara Clark and, because of the outbreak of war which was, according to Hoyle, going to make a nonsense of years of courtship, they were married by the end of that year.Hoyles work in astronomy was diverted during the war years as he was recruited by the Admiralty to work alongside Herman Bondi and Thomas Gold on secret project XRC8 concerned with the theory of Radar. Hoyle had previously obtained a fellowship at St Johns College, Cambridge and, after the war, he returned to St Johns as a lecturer. His research continued with Lyttleton on the theme of the formation and function of stars.

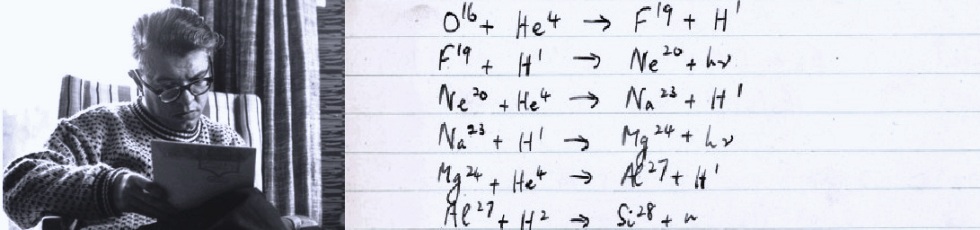

One of Hoyles most important contributions to astrophysics was his work on the formation of elements through nuclear fusion reactions in the stars including the origins of carbon. The culmination of this work was the seminal paper with William Alfred Fowler, Margaret Burbidge and Geoffrey Burbidge Synthesis of the Elements in Stars (known as the B2FH paper after the authors initials).Since Edwin Hubbles discovery, from observation of distant galaxies, that the universe is expanding, a theory about the origin of the universe was developed based on the concept that the expansion must have originated some time in the distant past at a single point. Hoyle strongly disliked this interpretation and developed an alternative theory (along with his long-term collaborators Hermann Bondi and Thomas Gold) based on the idea that the universe is, and always has been in a steady state and as it expands at a steady rate, matter is continually created in the vacuum. In a BBC radio broadcast in 1949, Hoyle delivered a public lecture in which he presented the ideas within the two theories. In describing the supposed explosive origin of the expanding universe as put forward by the rival theory he used the expression big bang.

The phrase caught on and ironically became the popular name to refer to the theory which eventually became the accepted consensus among the scientific community. Thats a consensus which excluded Hoyle, however, who stuck to the idea of the steady state model throughout his life despite growing evidence to support the big bang model.Hoyle had many other inspired and controversial ideas about cosmology and the origins of life some of which were literally science fiction. His most well-known novel, The Black Cloud published in 1957 was a showcase for the idea that life and even intelligent life may have originated in space.

After becoming Plumian Professor of Astronomy and Experimental Philosophy at Cambridge University and founding director of the Institute of Astronomy, Cambridge, Fred Hoyle was knighted in 1972. He died in Bournemouth in 2001 aged 86.

To find out more:

Publications:

Simon Mitton, Fred Hoyle: A Life in Science, Cambridge University Press, 2011

Burbidge, E. Margaret, Geoffrey R. Burbidge, William A. Fowler, and Fred Hoyle, Synthesis of the Elements in Stars, Revs. Mod. Physics 29, 547-650 (1957)

Fred Hoyle, The Black Cloud, Penguin Books

Website links:

Further information and an online exhibition can be found on the website of St John’s College Cambridge:

http://www.joh.cam.ac.uk/library/special_collections/hoyle/

A website dedicated to the life and work of Fred Hoyle:

http://www.fredhoyle.com/

Image credits:

[1] By kind permission of the Master and Fellows of St John’s College, Cambridge; [2] By kind permissions of Geoffrey Hoyle and the Master and Fellows of St Johns College, Cambridge

Main Image: Fred Hoyle c. 1965 [1] and Fred Hoyle’s handwritten notes on stellar nuclear reaction chains [2]

[Article © Yorkshire Philosophical Society 2012]